Translate this page into:

A Study on Spectrum of Clinical Variables on the Patients Attending Psychiatry Outpatient Department in a Tertiary Care Hospital

Corresponding author: Dr. Monu Doley, Department of Psychiatry, Assam medical college and hospital , AMCH Campus NEC Faculty Hostel , Dibrugarh, Assam, India. munudoley2017@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Doley M, Nath K. A Study on Spectrum of Clinical Variables on the Patients Attending Psychiatry Outpatient Department in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Acad Bull Ment Health. 2024;2:29-35. doi: 10.25259/ABMH_10_2023

Abstract

Objectives

The objective of the study is to determine the spectrum of clinical variables of the patients attending psychiatry OPD in a tertiary care hospital and to determine the association of those variables with various sociodemographic factors.The study was conducted in the psychiatric Out-patient Department(OPD) of a tertiary care hospital Barak Valley region in the Northeastern part of India.

Material and Methods

Retrospective observational study where we assessed 1827 consecutive patients asking for psychiatric services, attending psychiatry OPD of Silchar Medical College & Hospital in the one-year period. Out of a total of 1827 cases, 1200 cases were enrolled for the study, meeting the study criteria. Data regarding sociodemographic profile, duration of illness, and provisional diagnosis were also collected, and self-design proforma was used. For socioeconomic class Modified Kuppuswamy Scale is used. The patients were diagnosed and classified on the basis of ICD-10 Criteria by consultant psychiatrists. The patient’s complete profile and data were presented in tables with the use of Microsoft excel. The data obtained was entered and analyzed by using SPSS Version 21. Any case attending psychiatry opd with psychiatric problems and who were provided psychiatric services.

Results

Out of a total of 1200 patients, most patients were in the age group of 21–40 years, followed by 41– 60 years. The mean age is 34.5. Majority of them were male (59.4%) belonged to Hindu religion (56.08%),were married (44.41%),and educated upto primary school level (26.75%), living in nuclear family (64%), belonged to lower class socioeconomic status (33.5%). It was seen that the majority of the patients (31.25%) belonged to the ICD-10 category of F20-F29, and Schizophrenia (F20) was the most common diagnosis (21.75%). The majority of patients in diagnostic categories of F10-F19, F20-F29, F30-F39, F40-F48, G43, and G44, were in age group 21–40 years, while among MR and G40 were of age < 20 years. Looking at the individual diagnostic category, we found that the majority of the cases belonging to the categories of F10-F19 (19.49%), F20-F29 (35.20%), F30-F39 (14.02%), G40 (3.16%), G44 (14%), and others (2.24%) were males. while majority of cases having the diagnosis of F40-F48 (30.8%), MR (13.96%) and G43 (5.54%) were females.

Conclusion

This study has reflected the pattern of clinical variables of the patients attending the tertiary care center. It has helped us to understand the nature and extent of psychiatric disease burden in the community with an aim to facilitate designing and planning for providing better mental health care to the community as a whole.

Keywords

Clinical variables

psychiatry outpatient department

psychiatric illnesses

tertiary care hospital.

INTRODUCTION

The outpatient department serves as a nerve center for delivering healthcare services to individuals residing in a specific geographical catchment area. As with other disciplines, the psychiatry outpatient department lies at the core of the community effort to care for individuals with major mental illnesses.

The term psychiatry has its origin in the care of the mentally ill in state hospital settings.[1] The medical superintendents in the later half of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century expanded the domain of state hospitals and were eventually called “psychiatrists.”[1] In the latter half of the 20th century, there was an expansion in the scope of mental healthcare delivery with the incorporation of specialized nurses, clinical psychologists, and other caregivers.[2,3] The 1990s witnessed a paradigm shift, with consumers of psychiatric services coming together in the form of networks for peer support and advocacy.[4,5] With the passage of time, there has been a wider recognition of the pervasive burden that mental illness imposes on society. This realization resulted in increased funding for the strengthening of mental health care in tertiary centers. This will increase the integration between general medical care and psychiatry.[2,5,6]

The objectives of an effective mental healthcare model are to provide efficient, safe, and affordable mental healthcare services to a large population, along with a vision to upgrade existing infrastructure and enhance focus on prevention and promotion of mental health in the community.

The outpatient department of psychiatry provides services like assessment, diagnostic formulations, treatment planning, long-term management, and directions for clients seeking its services. It plays a specific role in the management of behavioral disturbances in individuals belonging to special populations, such as children and adolescents, defense personnels, forensic patients, the elderly, and those with medical comorbidities and developmental disabilities. The outpatient department also provides necessary emergency services, consultation liaison, community awareness programs, and programs for parents and caregivers. It is in this context that the current study attempts to investigate the clinical variables of all the patients attending psychiatry outpatient department (OPD)with the aim of evaluating a correlation of those variables with the socio-demographic profiles of those attending psychiatry OPD at a tertiary care hospital.

Aims & Objectives

-

To determine the spectrum of clinical variables of the patients attending psychiatry OPD in a tertiary care hospital.

-

To determine the association of those variables with various socio-demographic factors.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A retrospective observational study was carried out in a tertiary care hospital providing health services to the people of the Barak Valley region of North Eastern part of India.

Study period – from February 2019 to January 2020

Inclusion criteria

-

Consecutive new patients attending outpatient department of psychiatry over the study period.

-

Fulfilling International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), 10th revision (WHO, 1992) [7] diagnostic criteria.

Exclusion criteria

-

Follow-up cases.

-

Incomplete case records.

-

Major physical illness or chronic debilitating cases.

Data collection

The Institute’s Ethics Committee clearance was obtained, and then 1200 consecutive patients’ data were explored and extracted manually from the register book and history sheet of patients, at OPD Psychiatry. A sociodemographic profile, duration of illness, and provisional diagnosis were collected, and a self-designed proforma was used. For socioeconomic class, the Modified Kuppuswamy Scale was used. The patients were diagnosed and classified on the basis of International Classification of diseases (ICD-10) criteria by consultant psychiatrists. The patients’ complete profile and data were presented in tables with the use of Microsoft Excel. The data obtained was entered and analyzed using SPSS Version 21.

RESULTS

In this study, we assessed 1827 consecutive patients asking for psychiatric services and attending psychiatry OPD of Silchar Medical College & Hospital in a one-year period. Out of a total of 1827 cases, 627 cases were excluded, as 494 were follow-up cases, 83 cases had incomplete case records, 32 cases had their diagnosis deferred, and 18 cases were debilitated. So, 1200 cases were enrolled in the study that met the study criteria.

The distribution of specific demographic profiles of patients is tabulated in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 34.5, most of the patients were in the age group of 21–40 years, followed by 41–60 years. The majority of them were males (59.4%), belonged to the Hindu religion (56%), were married (44.4%), and were educated up to primary school level (26.75%). Illiterate people constituted 22.5%, high school were 20.5% of the sample, while unemployed people constituted 21.5% of the sample. 33.5% belonged to lower-class socioeconomic status. They belong mostly to nuclear families (64%).

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 1) < 20 yrs | 307 | 25.5 |

| 2) 21–40 yrs | 457 | 38.0 |

| 3) 41–60 yrs | 321 | 26.7 |

| 4) 61–80 yrs | 88 | 7.30 |

| 5) >80 yrs | 27 | 2.25 |

| Gender | ||

| 1) Male | 713 | 59.4 |

| 2) Female | 487 | 40.5 |

| Religion | ||

| 1) Hindu | 673 | 56.08 |

| 2) Islam | 481 | 40.08 |

| 3) Others | 46 | 3.83 |

| Educational Status | ||

| 1) Illiterate | 270 | 22.50 |

| 2) Primary school | 321 | 26.75 |

| 3) High school | 247 | 20.58 |

| 4) Higher Secondary | 209 | 17.41 |

| 5) Graduate and above | 153 | 12.75 |

| Occupational Status | ||

| 1) Unskilled | 88 | 7.33 |

| 2) Daily labor | 278 | 23.16 |

| 3) Unemployed student | 258 | 21.50 |

| 4) Servicemen | 204 | 17.00 |

| 5) Businessmen | 165 | 13.75 |

| 6) Retired | 73 | 6.083 |

| 7) Housewife | 89 | 7.416 |

| 8) Professor | 45 | 3.750 |

| Marital Status | ||

| 1) Single | 347 | 28.91 |

| 2) Married | 533 | 44.41 |

| 3) Widow/widower | 177 | 14.75 |

| 4) Separated/divorced | 143 | 11.91 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||

| 1) Lower class | 402 | 33.50 |

| 2) Upper lower class | 312 | 26.00 |

| 3) Lower middle class | 246 | 20.50 |

| 4) Upper middle class | 142 | 11.83 |

| 5) Upper class | 98 | 8.16 |

| Type of Family | ||

| 1) Nuclear | 768 | 64.00 |

| 2) Joint | 432 | 36.00 |

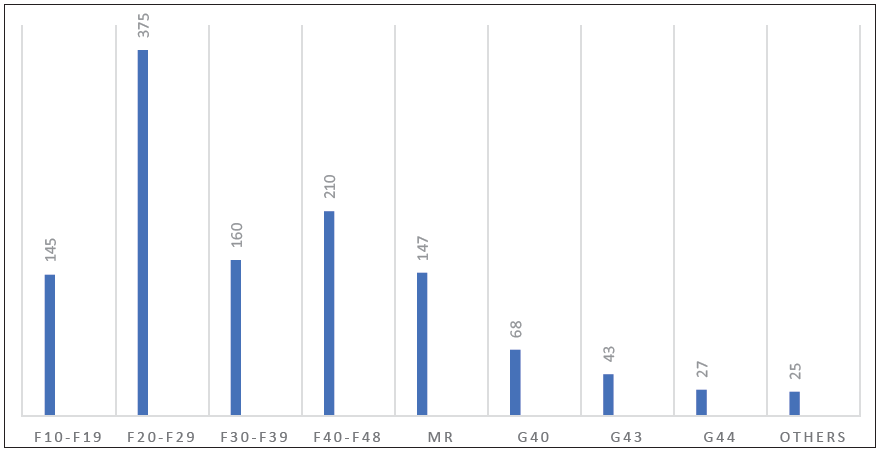

Tables 2.1 and 2.2 show the distribution frequency of psychiatric illness among the patients attending psychiatry OPD.It was seen that the majority of the patients (31.25%) belonged to the ICD-10 category of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20-F29) [Figure 1], Schizophrenia (F20) was the most common diagnosis (21.75%), followed by acute and transient psychotic disorders (5.5%) within the ICD-10 category of F20–F29. About 13.33% of patients were from Mood (Affective) Disorders (F30–F39) of which depressive disorder (F32) constitutes 6.83% and bipolar affective disorder (F31) constitutes 6.50%. Other headache (G44) patients constituted about 2.25%, and migraine headaches were about (G43) 3.58%. At the same time, 17.5% of patients had neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40–F48). Four percent were diagnosed with anxiety disorders, 3% had dissociative disorder (F44), and 5.75% had somatoform disorder. Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–F19) were 12%. We also found 12.25% of mental retardation cases, 5.66% of epilepsy (G40) cases, and 2.08% of other psychiatric problems.

| Diagnosis | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| F10–F19 | 145 | 12.08 |

| F20–F29 | 375 | 31.25 |

| F30–F39 | 160 | 13.33 |

| F40–F48 | 210 | 17.50 |

| F70–F79 (MR) | 147 | 12.25 |

| G40 (Epilepsy) | 68 | 5.66 |

| G43 (Migraine) | 43 | 3.58 |

| G44 (Other Headaches) | 27 | 2.25 |

| Others | 25 | 2.08 |

| Total | 1200 |

MR: Mental Retardation

| Diagnosis | Frequency (n) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Schizophrenia | 261 | 21.75 |

| 2) Acute and transient psychotic disorder | 66 | 5.50 |

| 3) Schizoaffective disorder | 48 | 4.00 |

| 4) Bipolar affective disorders | 78 | 6.50 |

| 5) Depressive disorder | 82 | 6.83 |

| 6) Anxiety disorders | 48 | 4.00 |

| 7) Dissociative disorder | 36 | 3.00 |

| 8) Somatoform disorder | 69 | 5.75 |

| 9) Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) | 21 | 1.75 |

| 10) Stress-related disorders | 26 | 2.16 |

| 11) Alcohol dependence syndrome (ADS) | 68 | 5.66 |

| 12) Opioid use disorders | 47 | 3.91 |

| 13) Multiple substance abuse | 30 | 2.50 |

| 14) Mental retardation(MR) | 147 | 12.25 |

| 15) Headaches | 70 | 5.83 |

| 16) Seizure disorders | 68 | 5.66 |

| 17) Other psychiatric disorders | 25 | 2.08 |

- Frequency Distribution of Psychiatric Illness.

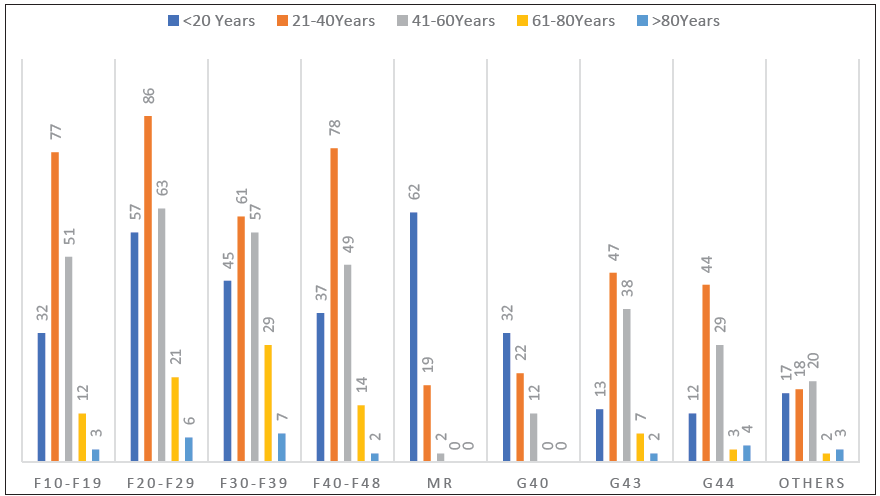

Table 3, along with Figures 2 and 3 shows the association and statistical correlation between the important demographic variables and psychiatric diagnosis made according to ICD-10. The majority of the patients in the diagnostic category of F10–F19, F20–F29, F30–F39, F40–F48, G43, G44, were in the age group 21–40 years, while those in the MR and G40 were of age < 20 years [Figure 2].

| Psychiatric Illness | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 713 | % = 59.41 | N = 487 | % = 40.58 | |

| F10–F19 | 139 | 19.49 | 6 | 1.23 |

| F20–F29 | 251 | 35.20 | 124 | 25.46 |

| F30–F39 | 100 | 14.02 | 60 | 12.32 |

| F40–F48 | 60 | 8.41 | 150 | 30.80 |

| F70–F79 (MR) | 79 | 11.07 | 68 | 13.96 |

| G40 | 38 | 3.16 | 30 | 6.16 |

| G43 | 16 | 2.24 | 27 | 5.54 |

| G44 | 14 | 1.16 | 13 | 2.66 |

| Others | 16 | 2.24 | 9 | 1.84 |

MR: Mental Retardation

- Distribution of Psychiatric Illness According to Age (In Years).

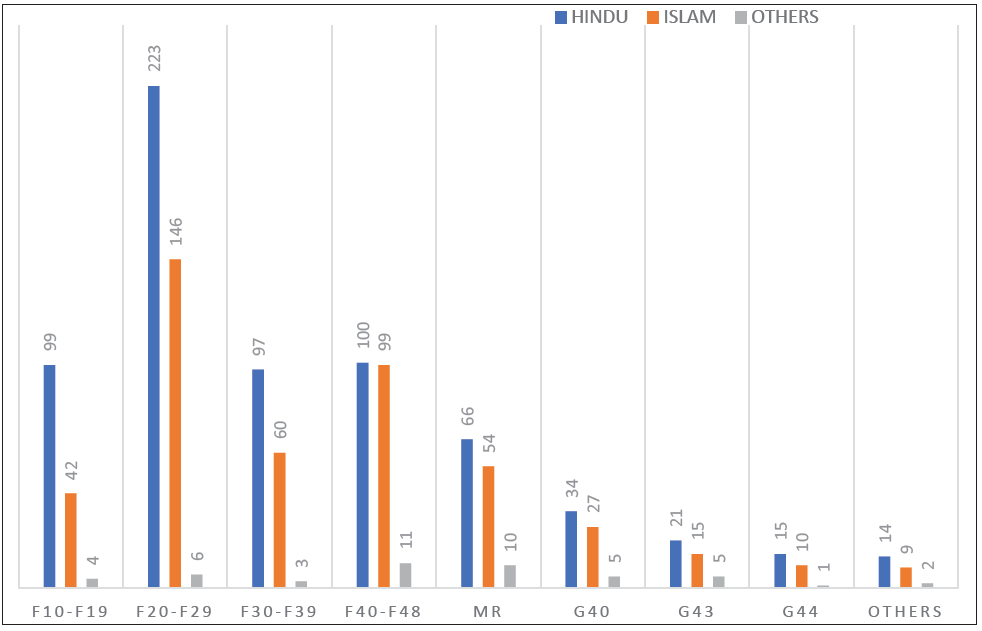

- Frequency Distribution of Psychiatric Illness Among Religion.

Looking at the individual diagnostic category, we found that the majority of the cases belonging to the categories of F10–F19 (19.49%), F20–F29 (35.20%), F30–F39 (14.02%), G40 (3.16%), G44 (14%), and others (2.24%) were males. While the majority of cases, the diagnosis of F40–F48 (30.8%), MR (13.96%), and G43 (5.54%) were female. In Figure 3, the distribution of psychiatric illness among religions reveals that Hindus outperform among all categories of psychiatric illness.

DISCUSSION

We found that the maximum of patients attending the psychiatric OPD in need of psychiatric services are in the age group of 21–40 years (38%). We found an almost equal distribution of patients seeking psychiatric services across gender and religion, with a slight male (59.4%) and Hindu (56.08%) dominance. It also reflects the population’s pattern. A similar study by Adhikari et al.[8] reveals that most patients in the age group of 21–40 years (45.73%), among them 59.25%, were males seeking psychiatric OPD services. Gupta et al.[9] also reported that most of the patients were in the 18–40 years (70.95%) age group, with almost equal numbers from both genders with a slight male predominance (73.2%). It may be due to the fact that patients of this age group are more concerned and have knowledge about health, leading them to seek healthcare services.

This study shows a higher number of male patients seeking psychiatric services compared to females, reflecting the gender differences in society. In the Indian context, most females are deprived of basic education, leading to low educational status, not being financially strong, and not being self-sufficient to seek healthcare services.

In our study, most patients are daily laborers (23.16%), unemployed (21.5%), married (44.41%), of lower socioeconomic status (33.5%), and live in a nuclear family (64%). A similar study by Sharan et al.[10] found that most patients are married (76%), unemployed (40%), of low socioeconomic status (68%), and seeking psychiatric OPD services. In Sharan et al.[10] study, most patients belong to a joint family (78%), in contrast to our study, in which most are from the nuclear family (64%). It may be due to low financial status, poor social support, and also high socio-economic status that people prefer to get treatment from private psychiatric settings. This group of patients attends government setup.

This study showed that most of the patients, 31.5%, who have been attending the psychiatric OPD are among the diagnostic category of F20–F29, 21.75% of the patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia, acute and transient psychotic disorders (5.50%), and schizoaffective disorder (4%). This finding is similar to the study by Kelkar et al.[11] (13%), Shahid et al.[12] (10.9%), and Bhatia et al.[13] (10.6%).

About 13.33% of the study population presented with Mood (Affective) Disorders with overall male predominance. Almost similar findings were reported in studies like Shakya et al.[14] (23%) from Nepal and Ang et al. [15] (23%) from Singapore.

We have found that 12.08% of the total cases presented with mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance abuse (F10–F19). These were significantly higher in males (19.49%) compared to females only (1.23%). This finding is close to Keertish et al.[16]

Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40–F48) constitute about 17.5%, of which 4% were anxiety-related, were dissociative 3%, and were somatoform 5.75%. Shakya et al.[14] from Nepal found almost similar results in their study subjects suffering from a neurotic and stress-related somatoform disorder.

Some cases were diagnosed to have non-psychiatric illnesses like epilepsy (G40), migraine (G43), and while patients presenting with other headache syndrome (G44) were at high rates (11.49%).

In our study, we found that the majority of the cases belonging to the ICD-10 category of F20–F29 were in the age group of 21–40 years. Adhikari et al.[8] and Kessler et al.[17] in their study also found that most cases in the age group of 20–39 years had psychosis. Mood disorders (F30-F39) are also more common among 21–40 years. This finding was similar to a study by Kessler et al.[17] which showed the median age of patients with mood disorders to be 30 years (20.87%). This signifies the onset of psychosis in this age group, which may be a more economically productive age group with more exposure to risk factors.

In the ICD-10 diagnosis of F40-F48 category, we also found that 17.5% of the cases were from the age range 21–40 years. Similar findings were found in Koirala et al.[18] study, which shows an age group of 16–40 years with neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders.

The occurrence of ICD-10 diagnostic categories in most cases belongs to the age range of 21–40 years. In this study, schizophrenia (21.75%) and depressive disorders (6.83%) are the most common psychiatric disorders, and the non-psychiatric illness most common is headaches (both migraine and other headache syndromes).

According to gender, most of the cases with an ICD-10 diagnosis presenting to the psychiatry OPD were males (59.4%), except F40–F48 were females (30.8%). Various studies, like Martin P et al.[19] and Trivedi JK et al.[20] suggest that stress-related disorders are more common in women.

Women are more likely to experience many stressors from early menarche to childbirth, which might lead to the precipitation of neurotic and stress-related disorders.

Many studies, like McHugh et al.,[21] Ammon et al.,[22] Lal et al.[23] show that substance abuse is more prevalent among males. In our study also, 19.49% were males compared to 1.23% of females. Income and societal status play major roles in substance abuse. Men are more likely to experiment with drugs, and have a low level of stigma, so they tend to seek treatment. In comparison, women carry more societal obligations and stigma less likely to seek treatment.

Not much gender difference is observed in psychiatric illnesses of category F20-F29. However, more male patients in the F30–F39 category (14.02%). As the male gender dominates society and, they are more frequently brought to the hospital. As a stigma to society, women with mental disorders have more stressors, social reasons, and negative life experiences in the catchment area, so they are less frequently brought to the hospital.

LIMITATIONS

As the study was a retrospective review of the patient’s profile, it may not reflect the exact data because people from all demographic areas, may not reach the tertiary care hospital. Moreover, this study was conducted only for a limited period of one year, so all the necessary information may not be available.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Mental health should be prioritized. More community-based studies on awareness, stigma of mental illness should be carried out. Integration of mental health to primary healthcare system is a must. Mental health disorders should be included in healthcare schemes.

CONCLUSION

In this study, most patients were in the 21–40 years age group and had schizophrenia as the most common diagnosis, followed by depression. It reflects how commonly schizophrenia is prevalent in society. Psychosis is most distressing to the community, marking the easy identification of symptoms compared to bipolar illnesses and depression, leading to the early seeking of mental healthcare services. Neurotic and stress-related disorders are more common among females in this study as women experience more problems in the family and social areas, leading to a lack of willpower. Lack of awareness of inappropriate beliefs has caused more harm to patients in desperate need, and decreased access to medical services by mentally ill patients has been related to several factors concerning the healthcare system.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Silchar medical College and hospital, number 01, dated 22/1/2018.

Declaration of patient consent

Patients consent not required as there are no patients in this study. Information was not collected directly from patients. Hence consent from the patient was not required.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no Conflicts of Interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI) assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

REFERENCES

- The State of the State Mental Hospital 1996. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC). 1996;47:1071-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dromokaition Psychiatric Hospital of Athens: From its Establishment in 1887 to the Era of Deinstitutionalization. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2015;14:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Ills and Bodily Cures: Psychiatric Treatment in the First Half of the Twentieth Century. Univ of California Press; 2023.

- DSM‐III and the Revolution in the Classification of Mental Illness. J Hist Behav Sci. 2005;41:249-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Philadelphia: lippincott Williams & wilkins; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. World Health Organization; 1992.

- Assessment of Socio-demographic Determinants of Psychiatric Patients Attending Psychiatry Outpatient Department of a Tertiary Care Hospital of Central India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3:764-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinico-Epidemiological Profile of Patients Attending Psychiatry Outpatient Department at State Hospital of Mental Health and Rehabilitation, Himachal Pradesh: A Northern State of India. Int J Res Rev. 2020;7:152-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of Socio-demographic, Clinical Characteristics and Prevalence of Perceived Stigma in Patients with Major Mental Health Disorders. MedPulse – Int Med J. 2017;4:239-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Study of Emergency Psychiatric Referrals in a Teaching General Hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:366.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Profile of Psychiatric Patients Presenting to a Tertiary Care Emergency Department of Karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:386-8.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Study of Emergency Psychiatric Referrals in a Government Hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:363.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric Emergencies in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2008;47:28-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric Referrals from an Accident and Emergency Department in Singapore. J Accid Emerg Med. 1995;12:119-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of Psychiatric Referrals in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Southern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1689.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Age of Onset of Mental Disorders: A Review of Recent Literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:359.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A Study of Socio-demographic and Diagnostic Profile of Patients Attending the Psychiatric Out-patient Department of Nobel Medical College Biratnagar. Journal of Nobel Medical College. 2011;1:45-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- An Overview of Indian Research in Anxiety Disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S210.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Sex and Gender Differences in Substance Use Disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:12-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Gender Differences in the Relationship of Community Services and Informal Support to Seven-year Drinking Trajectories of Alcohol-dependent and Problem Drinkers. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:140-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Use in Women: Current Status and Future Directions. Indian Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:S275.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]